An Article by

Frank D B.

A Consultant from Duesseldorf, Germany

Search Expertbase

Hire Frank D

Virtually

Hybrid

In-Person

POPULAR

Project Agility And Responsiveness - Maintaining The Informal Dimension

59 Claps

1136 Words

6 min

Traditional, rigorous project management methods are getting more and more insufficient. Business structures have become more ambiguous and fluid as technology has connected people globally. Critical knowledge is often fragmented and mostly available in its tacit form. Social Network Analysis (SNA) is one of the most accurate, systematic means yet seen to identify agile key value creators and informal knowledge structures.

In a world of constant change, traditional, rigorous project management and product development methods are getting more and more insufficient for success as Jim Highsmith, a recognized consultant and author on Agile Project Management, points out. Agility can be viewed as a characteristic that defines the quality of an organisation or project and is increased or decreased by management actions and attitudes.

In practice, agility is a careful balance between institutionalised control and carefully choreographed innovative interventions. Particularly in interdisciplinary and geographically-dispersed work settings one has to continuously align to changing situations. In these contexts, situationally specific strategies are often more appropriate than one-size-fits-all approaches.

Because agility cannot be bought or sold, advantage attained through agility is sustainable over time. Nevertheless, unquestioned rigidity, complexity and lack of visibility can prevent projects or organisations from being agile.

Focused collaborative exploration, flexible control strategies and identification of "invisible" informal assets using network analysis techniques can represent suitable approaches to manage these, sometimes interconnected, obstacles.

Collaboration and Knowledge sharing - Cornerstones of agile project management

Collaboration represents a "core managerial competency" and describes the trans-boundary integration of efforts across teams, functions, departments or organisations to achieve common goals. In general, this includes a high degree of communication and shared problem solution processes. One might ask: "Why all this collaboration now"? Business structures, whether formally hierarchical, networked or virtual, have become more ambiguous and fluid as technology has connected people globally. Critical knowledge is often fragmented and is turning more and more into a collective asset.

The transfer of knowledge is an interactive process and the nature of knowledge transfer is affected by the types of relationships people have. Knowledge workers in project teams must be able to navigate through a web of complicated social networks that exist around them, and are often only visible to those who know where to look. The extent that an individual’s "mental knowledge map" matches the actual knowledge network, directly affects their ability to forge relationships, and to gain access to new sources of knowledge. Most extant Knowledge Management approaches rely on static processes as well as on documents indexed by formalized meta-data and additional ontologies. However, these approaches are inadequate for highly dynamic and volatile business environments, whose activities cannot be sufficiently planned in advance and where new, unanticipated "knowledge needs" frequently arise. Such settings demand much more informal documents or artifacts and rely heavily on trustful personal communication between participants.

Cooperative-cum-competitive projects settings - Balancing compliance and commitment

As organisations or project partners engage in a fluidly evolving exchange process, they need adjustable and flexible control strategies. The intention to cooperate is translated into a relational contract that broadly outlines areas of exchange and codes of conduct. Dave Snowden from the Cynefin Centre warns that the formal organisation will always attempt to creep into other spaces through measurement and control, and this partially laudable endeavour needs to be controlled and channelled so that it does not inhibit the capacity of the team or organisation as a whole to develop to meet the demands of its environment.

In this context, Yogesh Malhotra, founder of the BRINT Institute, recognises self-control and commitment as the driver of human actor’s behaviour and actions across instead of emphasising unquestioning adherence to pre-specified rules or procedures. Instead of focusing on "best practices", his model encourages development of a large repertoire of responses to suggest not only alternative solutions, but also different approaches for executing these solutions. The proposed model is based on the premise that "solutions to problems cannot be commanded" [they] must be discovered: found on the basis of imagination, analysis, experiment, and criticism".

Informal networks - The "hidden" power in team-based work settings

People rely very heavily on their network of relationships to find information and solve problems - one of the most consistent findings in the social science literature is that who you know often has a great deal to do with what you come to know. Rob Cross of the University of Virginia points out that just moving boxes on an organisational chart is not sufficient to ensure effective collaboration among high-end knowledge workers. Movement toward de-layered, flexible organisations and emphasis on supporting collaboration in knowledge-intensive work has made it increasingly important for executives and managers to attend to informal networks within their organisations and projects. Communication density and complexity in these networks gets more challenging as the number and diversity of stakeholders (players with a stake in the outcome) grows. Nevertheless, performance implications of effective informal networks with respect to project agility can be significant as the rapidly growing social capital tradition has indicated at the individual, team, and organisational levels. Yet while research indicates ways managers can influence informal networks at both the individual, executives seem to do relatively little to assess and support critical, but often invisible, informal networks in organisations and projects.

Network Analysis techniques - Assessing and maintaining the informal social fabric

Social network analysis (SNA) comprises diagnostic tools that provide managers with both a visual map of the connections among individuals and quantitative data that substantiate the maps and their underlying patterns. Interviews conducted before and after the data gathering analysis ensure that the data are positioned in the context of the project and will not be misinterpreted or misused.

The data gathering and analysis processes provide a baseline against which one can plan and prioritise the appropriate changes and interventions that will increase the social connections within the organization or project - improving communications, knowledge transfer, collaboration, and mutual understanding of shared business goals. Focusing on project agility, SNA is one of the most accurate, systematic means yet seen to identify key value creators and informal knowledge structures that drive responsiveness and organisational core competencies.

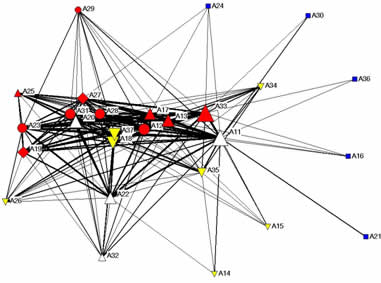

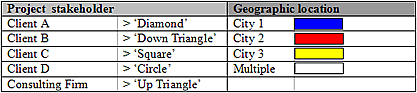

Figure 1 pictures an SNA example combining the visualisation of information and knowledge exchange relationships within a virtual project team with the indication of team member’s level of activity or "agility". Project stakeholders of this communal software development initiative are represented by different shapes, whereas the varying geographic locations are highlighted using distinct colours.

The graph clearly shows a separation between central and peripheral team members. In addition, two actors, thus "A33" and "A11" both belonging to the consulting firm, could be identified as most active individuals (indicated by shape size). Focusing on geographic project locations, it came apparent that the strongest relationships (indicated by line thickness) and prominent collaborative activities could be attributed to "City 2" (red colour).

Figure 1: Visualisation of information and knowledge exchange

This Article is authored / contributed by ▸ Frank D B. who travels from Duesseldorf, Germany. Frank D is available for Professional Consulting Work both Virtually and In-Person. ▸ Enquire Now.

Comments

What's your opinion?

1 more Articles by Frank D

59